Description

Maximize DHEA Skin Patch

Directions For Use: Apply One Skin Patch For 8 Hours Daily: (30-Skin Patches – 30-Day Supply)

DHEA – The Fountain of Youth And So Many More Benefits!

Dehydroepiandrosterone aka DHEA is not only the most abundant circulating steroid hormone in humans, it’s also the most underrated steroidal over-the-counter supplement your money can buy.

After the original hype around the “fountain of youth hormone” had abated and the pharma companies realized that there is no money to be made on a non-patentable naturally occurring agent, DHEA disappeared from the front pages of all major scientific journals (Olshansky. 2002). Without good reason, as the following overview of its proven and purported benefits is going to show.

DHEA and longevity, overall health and quality of life beyond the aging population – Although it may be true that the currently available evidence does not support the long-held notion that a couple of DHEA pill per day will prolong your life 5-10 years, there is conclusive…

- evidence that low levels of DHEA are characteristic of both, the normal and pathologic aging process and associated with rapid and severe cognitive decline (Barrett-Connor. 1994; Kalmijn. 1998; Carlson. 1999; Moffat. 2000; Davis. 2008; Sorwell. 2010)

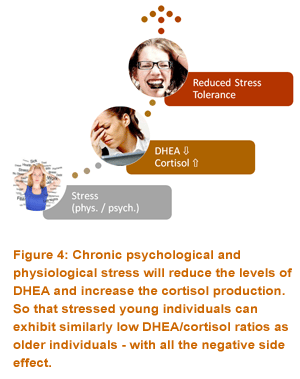

- evidence that low levels of DHEA are one of the proven characteristic of major depression in young and old individuals (Young. 2002; Angold. 2003) and “dehydroepiandrosterone may antagonize some effects of cortisol and may have mood improving properties” (Michael. 2000) – direct benefits have also been observed for anxiety and schizophrenia (Strous. 2003)

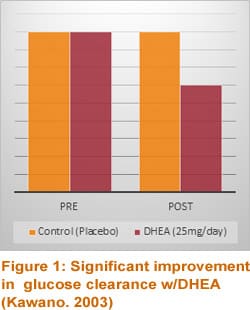

- evidence that low levels of DHEA are associated with an increased risk of diabetes (Yamaguchi. 1998) – an effect that is probably a direct result of the absence of the stimulatory effect of DHEA on muscular glucose uptake (Sato. 2008)

- evidence that low levels of DHEA are predictive of low libido in pre- and post-menopausal women (Guay. 2002; Morley. 2003)

Studies that investigated the protective & restorative effects of DHEA on cognitive and sexual functions, diabetes risk and overall health and quality of life in older individuals still yielded mixed results (Grimley. 2006). Flynn et al. (1999), for example, found no effect of DHEA replacement on the quality of life of postmenopausal women. Other researchers, however, found significant improvements in :

- Physical and psychological well-being for both 40-70 year-old men (67%) and women (84%) in response to 50mg of DHEA per day – probably in response to the normalization of the age-related decline in DHEA that occurred after only 2 weeks of daily supplementation,

- Symptoms of depression in 22 subjects with major depression in response to 90mg DHEA per day (Wolkowitz. 1999),

- Endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in middle aged men with mildly elevated cholesterol levels (Kawano. 2003) and elderly men and women in response to the daily ingestion of DHEA supplements (Villareal. 2004)

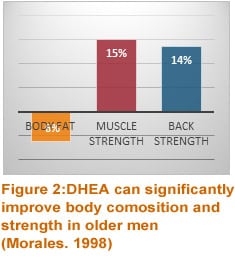

DHEA itself and its downstream metabolites, which include the major sex hormones testosterone and estrogen, have also been shown to induce significant improvements in bone strength in postmenopausal women and body composition in young and older individuals:

- Morales et al., for example, report significant reductions in body fat (-6.1 +/- 2.6%) and increases in muscle 15.0 ± 3.3%, as well as lumbar back strength 13.9 ± 5.4% strength in 50-65 year-old men in response to the provision of 100mg of DHEA per day (Morales. 1998) – without noticeable endocrine or neurological side effects, of course. Previous rodent studies showed similar improvements in body composition even in the presence of an obesogenic baseline diet (Hansen. 1997)

- Similar benefits as Morales et al. were also observed by Villareal and colleagues (2000) who found DHEA to be effective in improving boy composition (reduced body fat, increase lean mass) and bone density in post-menopausal women.

Figure 3: DHEA acts directly at the level of the fat cells to counteract obesity and optimize lipid

and glucose metabolism (De Pergola. 2000). Similar glucose sentitizing effects exist for muscle

cells, as well (Sato. 2008)

- In the so-called “DAWN” trial, von Mühlen et al. also found significant improvements in bone mineral density in their 55+ year old female subjects in response to 50mg of DHEA per day. In spite of the fact that the supplement was given for 12 months, no significant side effects were recorded (Von Mühlen. 2008).

The previous examples already suggested that the fact that age-induced decline in DHEA makes dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) particularly useful for older individuals does not imply that there were no benefits for those of us who have passed the 50 year mark, already – for example:

- Young resistance trainees may benefit from DHEA supplements, as well. Liue et al., for example, observed significant increases in the pro-anabolic hormone testosterone (100-300% increase depending on the age and baseline levels of the subjects; Liu. 2013) in a DHEA + resistance training intervention. And Liao et al. were able to show that DHEA will protect the musculature of hard training men and women from damage during super-intense workouts (Liao. 2012).

- Hamid et al. observed significant improvements in memory recollection and mood and decreased trough cortisol levels in young subjects after only 7 days on 150mg of DHEA per day (Alhaj. 2006).

- Reiter et al. saw significant improvements in all domains of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), a 15-item questionnaire that is used to rate the success of a given approach to treat erectile problems in response to 50mg of DHEA in a 24-week study without negative effects on the prostate cancer risk marker PSA (Reiter. 1999).

- DHEA has recently been identified as an effective treatment strategy for women with reduced ovarian reserve (Fusi. 2013) and may thus ” represent a first agent beneficially affecting aging ovarian environments.” (Gleicher. 2011) In this context it’s also worth mentioning that Hyman et al. were able to show that DHEA can improve the success rates of in-vitro fertilization (Hyman. 2013).

Low levels of DHEA, on the other hand, are associated with ischemic heart disease in middle-aged men in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (Feldmann. 2001) and will severe the side effects of corticosteroid treatments in inflammatory disorders (Kalimi. 1994; Straub. 2000). Apropos, DHEA has also been used successfully to…

- improve the chronic fatigue in patients with Addison’s disease, a pathology that’s characterized by chronically lowered cortisol levels (Hunt. 2000) and in women with non-Addisonian hypocortisolism (Arlt. 1999),

- reduce the number and severity of flare-ups in in female patients with systemic lupus, a painful systemic autoimmune disease that can affect any part of the body (Chang. 2002), and

- normalize sexual function and arousal in postmenopausal women (Hackbert. 2002)

Still, in spite of these and other proven benefits of DHEA supplementation and replacement, doctors all over the world still hesitate to suggest their male and female patients to give 3β-hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one (DHEA), as a chemist would say, a try.

Side effects – Your worries are unwarranted

The main reason for the aforementioned hesitations is the often-heard claim that DHEA, of which you’ve already learned that it can convert to testosterone and finally estrogen in the human body, would increase the risk of cancer. Based on the contemporarily available evidence, this claim does yet appears to be largely unwarranted. In fact, rodent studies have shown that dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the growth mammary carcinoma in rodents (Schwartz. 1979; Gatto. 1998) – a potential mechanism, i.e. the reduction of NADPH levels and the subsequent suppression of cancer growth has been identified by Schwartz et al. in 1995.

Epidemiological data on the association between breast cancer and DHEA is inconsistent, but Tworoger et al. report “[n]o associations […] between DHEA or DHEAS levels and breast cancer risk overall” in one of the more recent adequately powered studies (Tworoger. 2006). Similar results have been reported for pre- and postmenopausal women by Page et al. (2004) and Hankinson et al. (1998), respectively.

And what about men and high estrogen?

While cancer is certainly the worst-case scenario, many (young) men have been scared away from DHEA by the claim that it would increase their estrogen and lower their testosterone levels. Upon closer scrutiny of the pertinent data, it does yet turn out that this is another claim, which is – at least in men with an intact endocrine system –not supported by scientific evidence.

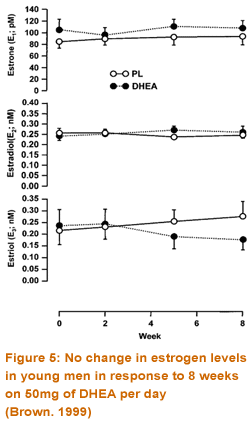

In 1999, for example, Gregory A. Brown et al. tested the effects of 50mg of DHEA on the hormonal response in exercising young men (23 +/- 4 years).

What the researchers found was a non-significant decline in estriol levels, – not a significant increase in serum estrogen (E2) levels , as the rumors would have it. Furthermore, neither the total nor the free testosterone or androstenedione (a precursor hormone) levels of the young study participants increased in the course of the 8-week treatment with 50mg of DHEA per day.

Almost identical results have been observed in middle-aged men in response to 100mg/day of DHEA. At the end of the 12 week study period which involved taking 2x50mg DHEA per day and participating in a standardized full-body strength workout, the scientists from the US States Sport Academy observed a non-significant increase in testosterone levels, no change in the prostate cancer risk marker PSA and non-significantly elevated increases in all measured parameters of training adaptation (power output, VO2max, bench press and leg press performance; Wallace. 1999).

References:

Angold, Adrian. “Adolescent depression, cortisol and DHEA.” Psychological Medicine 33.04 (2003): 573-581.

Arlt, Wiebke, et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in women with adrenal insufficiency.” New England Journal of Medicine 341.14 (1999): 1013-1020.

Barrett-Connor, Elizabeth, and Sharon L. Edelstein. “A prospective study of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and cognitive function in an older population: the Rancho Bernardo Study.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (1994).

Carlson, Linda E., and Barbara B. Sherwin. “Relationships among cortisol (CRT), dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS), and memory in a longitudinal study of healthy elderly men and women.” Neurobiology of aging 20.3 (1999): 315-324.

Chang, Deh‐Ming, et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone treatment of women with mild‐to‐moderate systemic lupus erythematosus: A multicenter randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial.” Arthritis & Rheumatism 46.11 (2002): 2924-2927.

Davis, Susan R., et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels are associated with more favorable cognitive function in women.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 93.3 (2008): 801-808.

De Pergola, G. “The adipose tissue metabolism: role of testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone.” International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 24 (2000): S59-63.

Feldman, Henry A., et al. “Low dehydroepiandrosterone and ischemic heart disease in middle-aged men: prospective results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study.” American journal of epidemiology 153.1 (2001): 79-89.

Flynn, M. A., et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone Replacement in Aging Humans 1.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 84.5 (1999): 1527-1533.

Fusi, Francesco M., et al. “DHEA supplementation positively affects spontaneous pregnancies in women with diminished ovarian function.” Gynecological Endocrinology 29.10 (2013): 940-943.

Gatto, V., et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the growth of DMBA-induced rat mammary carcinoma via the androgen receptor.” Oncology reports 5.1 (1998): 241-244.

Gleicher, Norbert, and David H. Barad. “Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation in diminished ovarian reserve (DOR).” Reprod Biol Endocrinol 9.1 (2011): 67.

Grimley Evans, John, et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation for cognitive function in healthy elderly people.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4 (2006).

Guay, A. T., and Jerilynn Jacobson. “Decreased free testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) levels in women with decreased libido.” Journal of Sex &Marital Therapy 28.S1 (2002): 129-142.

Hackbert, Lucianne, and Julia R. Heiman. “Acute dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) effects on sexual arousal in postmenopausal women.” Journal of women’s health & gender-based medicine 11.2 (2002): 155-162.

Hankinson, Susan E., et al. “Plasma sex steroid hormone levels and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 90.17 (1998): 1292-1299.

Hansen, Polly A., et al. “DHEA protects against visceral obesity and muscle insulin resistance in rats fed a high-fat diet.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 273.5 (1997): R1704-R1708.

Hunt, Penelope J., et al. “Improvement in mood and fatigue after dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in Addison’s disease in a randomized, double blind trial.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 85.12 (2000): 4650-4656.

Hyman, Jordana H., et al. “DHEA supplementation may improve IVF outcome in poor responders: a proposed mechanism.” European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 168.1 (2013): 49-53.

Kalimi, Mohammed, et al. “Anti-glucocorticoid effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).” Molecular and cellular biochemistry 131.2 (1994): 99-104.

Kalmijn, Sandra, et al. “A prospective study on cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and cognitive function in the elderly.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 83.10 (1998): 3487-3492.

Kawano, Hiroaki, et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation improves endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 88.7 (2003): 3190-3195.

Liu, Te-Chih, et al. “Effect of acute DHEA administration on free testosterone in middle-aged and young men following high-intensity interval training.” European journal of applied physiology 113.7 (2013): 1783-1792.

Michael, Albert, et al. “Altered salivary dehydroepiandrosterone levels in major depression in adults.” Biological Psychiatry 48.10 (2000): 989-995.

Moffat, Scott D., et al. “The relationship between longitudinal declines in dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations and cognitive performance in older men.” Archives of internal medicine 160.14 (2000): 2193-2198.

Morales, A. J., et al. “The effect of six months treatment with a 100 mg daily dose of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on circulating sex steroids, body composition and muscle strength in age‐advanced men and women.” Clinical endocrinology 49.4 (1998): 421-432.

Morales, Arlene J., et al. “Effects of replacement dose of dehydroepiandrosterone in men and women of advancing age.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 78.6 (1994): 1360-1367.

Morley, John E., and H. Mitchell Perry. “Androgens and women at the menopause and beyond.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58.5 (2003): M409-M416.

Page, John H., et al. “Plasma adrenal androgens and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 13.6 (2004): 1032-1036.

Reiter, Werner J., et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone in the treatment of erectile dysfunction: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.” Urology 53.3 (1999): 590-594.

Sato, Koji, et al. “Testosterone and DHEA activate the glucose metabolism-related signaling pathway in skeletal muscle.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 294.5 (2008): E961-E968.

Sato, Koji, et al. “Testosterone and DHEA activate the glucose metabolism-related signaling pathway in skeletal muscle.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 294.5 (2008): E961-E968.

Schwartz, Arthur G. “Inhibition of spontaneous breast cancer formation in female C3H (Avy/a) mice by long-term treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone.” Cancer Research 39.3 (1979): 1129-1132.

Schwartz, Arthur G., and Laura L. Pashko. “Mechanism of cancer preventive action of DHEA.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 774.1 (1995): 180-186.

Sorwell, Krystina G., and Henryk F. Urbanski. “Dehydroepiandrosterone and age-related cognitive decline.” Age 32.1 (2010): 61-67.

Straub, R. H., J. Schölmerich, and B. Zietz. “Replacement therapy with DHEA plus corticosteroids in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases–substitutes of adrenal and sex hormones.” Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie 59.2 (2000): 108-118.

Strous, Rael D., et al. “Dehydroepiandrosterone augmentation in the management of negative, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia.” Archives of general psychiatry 60.2 (2003): 133-141.

Villareal, Dennis T., John O. Holloszy, and Wendy M. Kohrt. “Effects of DHEA replacement on bone mineral density and body composition in elderly women and men.” Clinical endocrinology 53.5 (2000): 561-568.

Von Mühlen, D., et al. “Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation on bone mineral density, bone markers, and body composition in older adults: the DAWN trial.” Osteoporosis International 19.5 (2008): 699-707.

Wallace, M. BRIAN, et al. “Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone vs androstenedione supplementation in men.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise 31.12 (1999): 1788-1792.

Wolkowitz, Owen M., et al. “Double-blind treatment of major depression with dehydroepiandrosterone.” American Journal of Psychiatry 156.4 (1999): 646-649.

Yamaguchi, Yumiko, et al. “Reduced serum dehydroepiandrosterone levels in diabetic patients with hyperinsulinaemia.” Clinical endocrinology 49.3 (1998): 377-383.

Young, Allan H., Peter Gallagher, and Richard J. Porter. “Elevation of the cortisol-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio in drug-free depressed patients.” American Journal of Psychiatry 159.7 (2002): 1237-1239.